This website will be under development throughout 2018. Check in periodically for updates.

For useful and fascinating background reading to establish the socio-cultural context of this page: See The Literacy Wars by Ilana Snyder.

I wrote the paper at the bottom of this page for my library graduate diploma, six years ago. Since then, I have done a lot more work and training around marrying whole language and phonics approaches together, and helping them to serve their common agenda. Note that I didn’t say whole word, but whole language. Neuroscience has conclusively demonstrated that we don’t read by whole words (global word shape), but letter/sound by letter/sound:

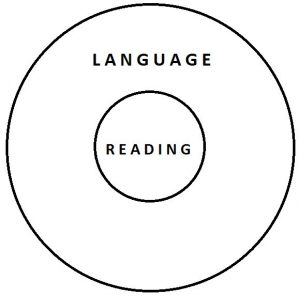

Phonics is fundamental to print decoding (reading), and is therefore especially important for kids with dyslexia, but print decoding is only one part of our experience with and use of language. Children require conversationally rich environments for their vocabularies and meaning-making to develop—and you will find that phonics advocates, like neuroscientist Dehaene, just as equally emphasise the importance of broad, immersive engagement with the whole of language, as they do phonics (eg, see the video above).  The best place to be situating your library work, in terms of reading acquisition advice for the public, is on the cusp between the wonderful work of Stephen Pinker in The Language Instinct, and the wonderful work of Stanislas Dehaene in Reading in the Brain. (Because, following on from Snyder’s analysis of conflicting literacy beliefs, I think there are some pervasive misconceptions about a supposed incompatibility between some of Pinker’s and Dehaene’s conclusions, and that’s what gets people unstuck. More on that to come.) Pinker’s work is largely about our spoken and mental language faculties, which are indeed “instinctual”, or built into us, and Dehaene’s work is about our written language capacity, which requires forging pathways in the brain between sound and vision, and which, interestingly, uses neuronal recycling of the face-recognition brain areas for application in word recognition. Think about it this way: Language is the umbrella concept, and reading is a part of it. So for example, an adult who can’t read has mastered language through speech/listening, but not reading/writing. They have cracked the spoken code, but they have not cracked what Debbie Hepplewhite calls the Alphabetic Code. Here’s another video by the captivating Dehaene, plus a brief summation of our language instincts by Stephen Pinker, below.

The best place to be situating your library work, in terms of reading acquisition advice for the public, is on the cusp between the wonderful work of Stephen Pinker in The Language Instinct, and the wonderful work of Stanislas Dehaene in Reading in the Brain. (Because, following on from Snyder’s analysis of conflicting literacy beliefs, I think there are some pervasive misconceptions about a supposed incompatibility between some of Pinker’s and Dehaene’s conclusions, and that’s what gets people unstuck. More on that to come.) Pinker’s work is largely about our spoken and mental language faculties, which are indeed “instinctual”, or built into us, and Dehaene’s work is about our written language capacity, which requires forging pathways in the brain between sound and vision, and which, interestingly, uses neuronal recycling of the face-recognition brain areas for application in word recognition. Think about it this way: Language is the umbrella concept, and reading is a part of it. So for example, an adult who can’t read has mastered language through speech/listening, but not reading/writing. They have cracked the spoken code, but they have not cracked what Debbie Hepplewhite calls the Alphabetic Code. Here’s another video by the captivating Dehaene, plus a brief summation of our language instincts by Stephen Pinker, below.

The general principles of whole language engagement are economically summarised in the 3a Language Priority, Enriched Caregiving, and Conversational Reading family guides. One way to think about phonics approaches to reading is to note the 3a LearningGames. These demonstrate the various pattern finding strategies that children develop across all areas of learning and intellect, and in that light, you can see how sound (speech) and sign (print) awareness games are simply auditory and visual pattern finding learning strategies, just like 3a’s LearningGames. On this site, I call the specific phonemic awareness versions, Reading Games, and have begun adapting the games as readers, for kindergarten and prep families to conversationally “play”, parent and child together.

Note that the six-year-old paper below hones in on advocacy for phonics specifically—the side of the debate that I felt was lacking in library practice and products at that time. What is ultimately planned for this web page is a far more holistic marriage between the two than the old paper below, using a lot of this early literacy science. In the meantime, to balance out the paper below, consider this video of whole language and phonics approaches working together like interwoven DNA. What is also only minimally addressed in the literature review below, but is nonetheless central to my work, is parent empowerment. In lieu of more content—to come—about the potential for peace in the literacy wars for the sake of parent empowerment, you can find some reflections on parent education on the Babytime program page.

The Sky is the Limit for Preschool Storytime, So Let’s Soar (2012)

Trends in computer and telecommunications technology are likely to push the public library out of its traditional markets … sometime in the next century. If the public library is not to become marginalized, it needs to begin to move aggressively to develop services which address the educational needs of children and youth … Public libraries in the 21st century can own the preschool education market, if they decide today to develop and concentrate on serving this market. This means much more than the typical fare served up by most public libraries: the picked over selection of aging, rag-tag books and the once a week storytime (Scheppke, 2007, p.35 & 38).

Introduction: A Missed Opportunity

The passion and curiosity with which I have undertaken this study springs as much from the part of me that thinks like a parent as it does from my inner librarian. My son and I have attended, over the past two years, preschool storytime[1] (PS) sessions at the public library services of four Melbourne city councils (encompassing twenty-two branches, twenty of which conduct PS), as well as the State Library of Victoria. During these same two years, my son has participated in synthetic phonics classes (Jolly Phonics)—which he adores, and from which his reading has benefited profoundly. As a consequence of these experiences, I became compelled to investigate whether there is existing advocacy for layering PS with reading instruction principles (there is), and consequently what barriers are preventing the implementation of such educational strategies.

Scheppke, in the above epigraph, advocates for children’s librarians to take on a more pedagogical role for pragmatic, business reasons—and his are sound and persuasive arguments. In the financial year 2009-10 alone, 44 Victorian council library services ran 26,203 program sessions for children and youth, attended by 696,642 people (Victorian Department of Planning and Community Development, n.d.)—a sizeable market indeed. But for me, the pragmatic reasons are simply the icing on the cake; I prefer Herb’s (2012) rather lofty and admittedly hyperbolic take on the issue: ‘In an ideal world the preschool storytime deliverer should be as respected and valued as the brain surgeon. It is that important’ (para.43, my italics). Herein, I discuss the need to elevate the current climate of PS service delivery to equal its social importance.

The Experiential Difference Between Preschool Storytime & Phonics Lessons

There is so much that is similar in principle and practice between these two activities (PS and phonics instruction), yet while phonics classes include storytelling/literature, PS rarely introduces phonics/explicit reading skills. Clearly, the two services could never be exactly the same. Private phonics classes have a maximum capacity (and therefore a manageable teacher-to-child ratio—which usually includes a teaching assistant). Due to small classes, the children are afforded far more opportunity to speak up, engage, and receive one-on-one attention from the teacher as required. (See serve and return brain architecture.) The children in phonics classes are committed to and regularly attend the weekly classes, and so all have roughly the same level of experience. The parents have signed enrolment forms and engaged in a duty-of-care contract with the phonics class providers, and can leave their children in the care of the teachers (preventing the distractions that come from parental—and possibly younger siblings’—presence). But the fact remains that each activity from a typical phonics class could be incorporated in some—if necessary, modified—measure in PS. Similarly, there is no reason why the inclusion of phonics activities should decrease the attention to literature in the session—the activities are undertaken in the context of the literature, and in fact draw the children into further engagement with the chosen books.

Can & Should Preschool Storytime Transmit Reading Skills?

Celano and Neuman made an excellent point back in 2001: ‘Educators often assume that library programs promote children’s literacy, but few studies have measured their impact on preschool and elementary school children’ (p.11). Kupetz (1993) and Fehrenbach, Hurford, Fehrenbach and Bannock (1998) found that library outreach programs significantly increased the emergent literacy and reading capacity in preschool groups compared to control groups[2]. There has, however, been scant research on everyday PS specifically (favouring research on specialist interventions), despite Dowd urging for it in a 1997 paper (and others since)—however, there have been many literature reviews, meta-analyses and/or theoretical papers written[3], which all argue that developing literacy in children (and literacy enhancement skills in parents) ‘should be a primary role of the young people’s services librarian’ (North, 2000, p.52).

What has been carried out in abundance is related research about early literacy in the fields of early child development, education and psychology[4], and thus it has become common to claim that ‘research has shown that library storytimes can make a difference!’ (MacLean, 2008, p.8) on the basis of early literacy research in these other fields–which is a completely fair thing to deduce; science from related fields is better than no science! However, many of the renowned, frequently-cited articles on the topic of PS and literacy commonly use the phrase ‘best practice’ rather than ‘evidence-based’[5], perhaps linguistically reflecting the fact that there is a lack of direct evidence either for or against the ability of public library PS to enhance children’s literacy development.

McKend (2010) points out that ‘it is challenging to isolate early literacy storytime programs as the definitive factor affecting reading readiness in most cases’ (p.18). Diamant-Cohen, Riordan and Wade (2004) similarly emphasize that many programs rely on standardized testing to measure children’s progress, even though ‘brain research suggests that the learning process is too complex and varied to be accurately measured for all children by a standardized test’ (p.19). However, as McKend (2010) admits, researchers and practitioners could collaborate in devising methods to account for these challenges. Additionally, according to Rosenthal (2004), there has traditionally been a ‘reluctance exhibited by library professionals to quantify and measure the benefits of providing children’s programming’, but she nonetheless believes that this ‘is beginning to lift and the climate of accountability is affecting the public library community’ (para.12). Walter (2003) similarly asserts that ‘more recently, policymakers and funding sources have started to request a more sophisticated form of evaluation measures’ (p.582)—in other words, they are seeking outcome measures[6] rather than simply measures of output[7]. Perhaps the climate (and pressure) now exists to begin measuring the impact of PS. While the evidence from other disciplines discussed above does fill one with confidence that quality PS sessions would have a positive impact on children’s literacy, it is hard to apply pressure to organisations, staff and funding bodies to adopt a practice without direct evidence of its efficacy.

Why Synthetic Phonics?

There is, however, a plethora of evidence for the strength of synthetic phonics programs in empowering children to decode words, ie, read (e.g., Byrne & Fielding-Barnsley, 1989, Byrne & Fielding-Barnsley, 1985, Hatcher, Goetz, Snowling, Hulme, Gibbs & Smith, 2006). There have been some particularly strong studies, with large samples and good controls, many of which have had a significant impact on government advisory panels and education policy (e.g., Johnston & Watson, 1998, Stuart, 1999, Sumbler & Willows, 1996, Watson, 1999, Johnston & Watson, 2005). The standing recommendation to the Australian[8], US[9] and UK[10] governments is to implement synthetic phonics in kindergartens and primary schools as a key strategy in teaching children to read.

And while the focus of the present study is largely on research supporting the use of phonics and formal literacy strategies in storytime, it should be noted that

some components of emergent literacy cannot be developed apart from meaningful print. Although other components, such as letter recognition and phonological awareness, can be developed in isolation, it is important that these skills be connected to print in order to motivate children and prepare them to apply these skills to print in purposeful and meaningful ways (Allor & McCathren, 2003, p.75).

Gambrell, Morrow and Pennington’s (2002) literature review supports that high quality literature is paramount to literacy instruction. If both activities (storybook reading and phonics) enhance each other, there exists a strong argument for PS as an ideal vehicle for them to be explored concurrently. However, it is worth noting Aram and Biron’s (2004) study involving three groups of preschoolers—a writing group (‘letter knowledge, phonological awareness, and functional writing activities’), a reading group ‘utili[sing] 11 children’s books for focusing on language and exploring major concepts raised by these books’) and a control group. Although, at the end of the study, both experimental groups’ literacy skills far exceeded the control group’s, ‘the joint writing group significantly outperformed both the joint reading group and the control group on phonological awareness, word writing, orthographic awareness, and letter knowledge’ (p.588). Based on their review of similar research, McGee and Schickendanz (2007) agree ‘that merely reading books aloud is not sufficient … Instead, the way books are shared with children matters’ (para.1, my italics).

Is Letting the Kids Speak Up Akin to Opening Pandora’s Box?

Celano and Neuman (2001) discuss the recent shift in CLS (particularly for babies and toddlers[11]) from reading readiness (preparation for formal reading instruction) to emergent literacy. ‘In emergent literacy techniques, children are encouraged to tell their own “stories,” “write” their own ideas, and perform their own “dramas” as a way to foster their early reading skills’ (p.12). However, the ‘typical fare’ storytimes, to use Scheppke words, in my experience as a customer, rarely seek children’s involvement in this way. Similarly, MacLean (2008), in her analysis of PS and literacy scholarship, found that ‘there [is] general agreement in the literature of six pre-reading skills that children must have before they can learn to read’ (p.3). Nonetheless, in most Victorian PS sessions that I have attended, only print motivation (‘thinking that books and reading are fun’) and vocabulary (‘knowing the names of things’) are explicitly addressed. Print awareness (‘recognizing print and understanding how books work’) may be absorbed by children implicitly, through observing book reading, but rarely is attention drawn to the lettering on the page, nor do the librarians often name or discuss the author or other non-narrative/non-illustrative properties of a book. Children would absorb the most rudimentary level of phonological awareness (‘being able to recognize and play with the smaller sounds that make up words’) when read stories or are lead in songs involving rhyming or wordplay, but again, no formal pedagogy is applied to phonetics. Letter knowledge (‘understanding that each letter has its own name and sounds’) is only conveyed, in my experience, when the children are read alphabet books (e.g., Dr Seuss’ ABC) or sing the alphabet, which is infrequent/irregular. And finally, narrative skills (‘being able to tell stories and describe things’) is partially addressed, insomuch as children may be asked closed questions on the theme (e.g., ‘where do you go with your grandparents?’, or ‘have you been to the zoo?’). But these responses are expected to be, or kept, brief; that is to say, children are invited to name, confirm, or deny, but rarely allowed the time, forum or structured activity to explore narration or extended discourse.

As McGee and Schickendanz (2007) point out, ‘research has demonstrated that the most effective read-alouds are those where children are actively involved … rather than passively listening’ (para.1). For example, Wasik and Bond (2001) found, using an interactive book reading technique, that children who were given ‘concrete objects that represented the words and [provided] with multiple opportunities to use the book-related words … scored significantly better than children in the comparison group’ (p.243). Clarke-Stewart (1998) adapted pre-adolescent books so that they contained simplified passages children could read themselves, and found that ‘compared to merely listening to their parents read the original stories, children benefitted from taking turns reading the adapted text with their parents in terms of enjoyment, attention, and reading fluency’ (p.1, my italics). And enjoyment, many agree, is as fundamentally important as the literacy skills themselves: ‘Librarians are in their own way teachers … teaching children how to love to read. By making literacy fun, they set the early literacy foundations needed for reading success’ (MacLean, 2008, p.9). Which is not to say that the current ‘typical fare’ is not fun, but I have been astounded at the level of concentration and engagement that my son’s phonics teachers have been able to encourage in a band of energetic 3 to 5 year olds; whereas in my observation, the children in PS rarely attend to the librarian at that same level of engagement for the entire session. (This also relates to knowledge and skills in the area of group facilitation with adults as well, since any children’s librarian will tell you that whether parents are deeply engaged or deeply disengaged, they nonetheless have a significant impact on the session—just for different outcomes.)

Nichols’ (2011) geosemiotic investigation of children’s library spaces points out that, during PS,

An unwritten rule is that the collective’s focus on the presenter should not be undermined by intrusive forms of parental discipline. On the other hand, the presenter should not be expected to divert from her activities to discipline a child. One can imagine families for whom this set of expectations could be problematic, either because parents use overt rather than covert forms of discipline or because teachers (the librarian is in this role) are expected to control children without the support of other adults (p.187).

The lines often seem to be blurred about who (parents or librarian) is responsible for what in terms of the PS dynamic. Similarly, there is often a perceptible nervousness about allowing children to participate, get excited, take the lead, and tell detailed stories, as though heavy-handed crowd control is needed or it will get out of hand. This, certainly for me as a parent, translates into a nervousness about keeping my child subdued. The relationship between the presenters’ confidence/leadership and the parents’ ease/involvement/satisfaction, or the children’s responsiveness/progress, would be a worthy area for further research. It would similarly be fruitful to ask librarians exactly what the barriers are to soliciting conversational exchanges with the children—is it a ‘crowd control’ fear, or a belief that the session should be about the story above all else? Is it not wanting to give too much time to certain children, and offend/bore other parents and kids?

Storybook reading is a more effective influence on literacy development when children have opportunities to engage in conversation about the story. This research–supported finding runs counter to actual preschool storytime practice. How many of us have tried to cut off conversation during storytimes to “get back to the story?” (Herb, 2012).

Other questions worth asking are whether a major barrier to best practices is simply the fact that librarians need better preparation/training in managing large groups of very young children and their adult carers, or whether clear guidelines for parents need to be established so that presenters can relax.

Could Librarians Themselves Present as Unwitting (or Wilful) Obstacles?

In 1983, Gibbs wrote an impassioned and reasoned plea for children’s librarians to have special training in the ‘psychology of the child, including reading development and tastes’ (p.202), and for library courses to include the option of such a specialisation. Herb (2012) similarly advocates for ‘experienced children’s librarians whose areas of speciality include early childhood education and child development’. And yet, although the Australian Library and Information Association (2010) recommends that children’s librarians should ‘be committed to developing knowledge of young people’s material by wide reading, in-service training and networking and attendance seminars’ (para.4), qualifications in child development and education are not necessarily a requirement. While Adkins and Higgins (2006) found that Australian librarianship courses include children’s service delivery specialisations (the ‘library’ part of the job), the study did not indicate whether early development and the formal teaching of literacy where covered in these units[12] (the ‘education’ part of the job)—although it did suggest, on the basis of the findings, that ‘foundational knowledge of educational … policy’ (p.45) would be a worthwhile addition to courses.

As is the trend in this topic, we can perhaps borrow findings from other fields (teaching/education) to gauge the likelihood of librarians having sufficient training and knowledge about teaching phonics/systematic literacy approaches. The Department of Education, Science and Training’s (2005) Teaching Reading report found that in primary teaching degrees, ‘less than 10 per cent of course time is devoted to preparing student teachers to teach reading. They also indicate that in half of all the nominated courses less than five per cent of time is devoted to this activity’ (p.113). Interestingly,

Many institutions offer elective subjects/units in which the teaching of reading is a component. In almost all cases respondents judged that these electives substantially or considerably enhanced preparedness to teach reading. It seems, therefore, that some graduates are better prepared than others to teach reading because they have completed such electives. In light of how important it is that children learn to read and continue to develop their literacy skills to access the curriculum throughout their schooling, this raises the question of why these are elective subjects/units rather than compulsory subjects/units (p.113).

One might say a similar thing of children’s librarianship. As far as those already working in the industry are concerned, perhaps a professional development program like On the Road to Reading (‘a bookmobile program’ in which ‘teachers learn the foundation of ECRR and the six preliteracy skills’ [Fulton, 2009, p.8]) would be of benefit.

Hamre, Justice, Pianta, Kilday, Sweeney, Downer and Leach (2010) tested the fidelity of early childhood teachers’ implementation of recommended teaching methods. They found that while teachers frequently adhered to the curriculum, there was a lower rate of fidelity in terms of quality (‘use of evidence-based teacher–child interactions for teaching literacy and language’ [p.329]). One can hypothesise a number of reasons for this, such as personal beliefs about, or support of, the evidence-based practices. For example, there is vehement debate surrounding phonics versus whole language approaches (Nicholson & Tunmer 2011), despite the two things being complimentary, not mutually exclusive. When the Australian government commissioned Teaching Reading report was released, which recommends synthetic phonics, the head of the inquiry, Dr Rowe, ‘said he was dismayed by the defensiveness of some education leaders. He urged all politicians, principals and teachers to read the report before passing judgement on its recommendations’ (Milburn, 2006, para.5). (He went on to reassure that ‘“the inquiry is not suggesting that phonics is the be-all and end-all in learning to read, but it is fundamental. The sad thing is that we do not have enough people in this country trained to teach it explicitly and systematically”’ [para.7].) Hindman and Wasik (2008) found that preschool teachers generally agreed in their approaches to oral language and book reading, but varied in their opinions about the teaching of phonetic, alphabet and writing knowledge. They did find, however, that more experienced teachers were more likely to agree with research-based practice, suggesting that with more education and experience, children’s librarians, like teachers, may be more inclined to follow storytime best practices and embrace phonics approaches, despite any initial biases. Perhaps with experience, teachers overcome preconceived biases and recognise that

although children need direct instruction to gain [phonetic] skills, the skills are not reached through drills, but by engaging them in fun, interactive, age-appropriate activities … Repeated reading of rhymes, poems, or stories with rhyming words help children notice sound patterns. Clapping out syllables in their names or characters in a book helps children begin to separate sounds in words. Other fun games include searching for things on a page that begin with the “n” sound or singing songs like “Willoughby Wolloughby Woo” to heighten awareness of speech sounds…Libraries are well suited to provide this amount of instruction as part of existing programming” (Arnold, 2003, p.50).

In my experience of the two, as I implied at the outset of this review, the two activities are not drastically different. Fader (2007) points out that ‘storytimes that incorporate these practices differ in subtle ways’ from ‘typical fare’ storytimes—‘building in the early literacy information does not change the basic nature of these programs’ (p.1).

Another barrier to value-added, literacy/phonics-based PS may be a feeling amongst librarians that such instruction is not within their job description—one respondent in Bing’s (2009) series of interviews believed that teaching people to read should not be children’s librarians’ responsibility, since they are not trained teachers, and that the Ready to Read project was ‘pushing librarians to teach parents to teach their children to read’ (p.72). The majority of respondents, however, were enthusiastic about their role in children’s (and parents’) literacy—‘storytimes illustrate to parents just how easy it is to connect with children through literacy’ (p.67).

What Do The Patrons Themselves Want and/or Need?

A number of theorists agree[13] (based on empirical findings) that since parents have the greatest impact on their children’s literacy, the key goal of PS is to educate parents (MacLean, 2008, Cerny, Markey & Williams, 2006, Ghoting & Martin- Díaz, 2006). Raban and Nolan’s (2005) survey of Victorian parents of preschoolers in disadvantaged areas found ‘that parents read to their children regularly from a young age, found libraries easy to access and use, and have children who enjoy books and paper and pencil activities. However, more than half of them found there was not enough information available to support them in their child’s literacy development’ (p.289). If these parents are finding libraries easy to access (bearing in mind that ease of access does not translate into actual attendance), then the effectiveness of the ALA[14] and the NICHHD’s[15] initiative, Every Child Ready to Read @ Your Library, suggests that value-added storytimes in which the librarian demonstrates useful strategies and educates the parent as to why the strategies are effective would ‘significantly increase their literacy behaviours’ (MacLean, 2008, p.6, citing results from Laughlin, 2003).

In terms of the parent as client, Carlson & Stenmalm (1989) concluded, as a result of their survey of parents’ versus professionals’ expectations of early childhood programs, that parents and professionals ‘need to discuss a common purpose and philosophy about what is important for young children in early childhood programs’, and that ‘this purpose needs to take seriously the societal context in which children live’ (p.51). No detailed, qualitative study has been undertaken (in Australia or elsewhere) of parents’ reactions to specific aspects of the ‘typical fare’ storytime, nor of their needs or wishes in regard to PS. Australian parents/adults have been provided with satisfaction surveys by individual libraries (Bundy, 2007, p.178)—these results are obviously not publicly available. Parents have been surveyed after their involvement in literacy enhancement library programs, specifically about their children’s literacy progress, and about how their own literacy behaviours (e.g., reading aloud) may have changed/improved since the program (e.g., Laughlin, 2003). In very general terms, The State Library of Victoria with the Library Board of Victoria (2004) applied a gap analysis[16] in their public library users’ satisfaction survey, finding ‘scope for improvement in children’s and young adults’ services, school holiday programs and storytime. While libraries satisfy users with these services, the scores suggest that libraries could either offer more of these services or a higher quality of service’ (p.36). A more detailed survey about specific aspects of PS, perhaps both of children’s librarians and parents for the purpose of comparison, may shed important light on exactly what parents want from the service delivery of PS, and how well our storytimes are targeting those needs—supplying to that family-centred demand.

In terms of the child as client, what children want from a service is not always what adults want for them: in Munde’s (1997) survey of children’s and adults’ responses to 168 humorous books[17], only six titles were chosen by both adults and children. Munde concluded that ‘there is a disparity, perhaps irreconcilable, between the humorous books children choose to read and the humorous books adults choose for children to read’ (p.219). Bundy (2007), on behalf of FOLA[18], asked Australian public libraries via survey, ‘Have you ever formally surveyed the satisfaction of children and young people with your library services?’, and 91% responded ‘no’ (p.4). The unfortunate side-effect of this lack of feedback from children, coupled with a lack of adequate training in the literacy research based for library practitioners, is that most librarians don’t know this information. They don’t know that out of 168 humorous books, adults will only tend to agreed with children’s tastes in book selection about 6 times. If a librarian isn’t empowered with this knowledge, they can’t use the knowledge to select better, more motivating books for children. Which means they will connect with children’s book tastes less than people who do have that knowledge. However, what we then tend to sadly assume is that some librarians “just have that spark” with children, whereas some “just don’t”, and this is unfair to our librarians. Everyone is capable of growing their skills with adequate support and information.

‘That Old Chestnut’: Resource Barriers

Marshall and Strempel (2009) claim that ‘most of the literacy based activities, services, programs and collections delivered by public libraries are operated on shoestring budgets or via grant funding from various agencies such as State Libraries’ (p.3). Bundy’s (2004) survey of Australian public libraries found that librarians cited ‘lack of funding and staff time’ as the ‘major constraints’ to introducing a Bookstart-type program[19] (p.196), and the librarians who responded to his 2007 survey similarly claimed that there are often ‘no staff designated to run programs, so they are done in an ad hoc fashion’ (p.179). Indeed, my experience that Victoria PS programs could benefit from value-adding may relate to the fact that Victoria public libraries have had lower spending per capita, at least for the last five years, than the national average for the given year (State Library of Queensland Public & Indigenous Library Services 2011). Furthermore, Fisher (2000) found that the proportion of library funding spent on the 0-18 age group rarely matches the proportion of these young people in the community.

Juggling resources, including human, is a tricky business. As discussed, a barrier to high-quality PS is overcrowded sessions, which one library solved by using parent volunteers (Sherman, 1998). But this is not necessarily an option if the intention is to incorporate formal, specialist literacy teaching principles in sessions. Where one problem is solved, another appears. Overcrowding makes it difficult for children to hear and see, an obstacle which could potentially be overcome by using innovative audio-visual technology—though this is potentially taboo in a library context (perhaps a little too much like television for many a librarian’s liking). However, preliminary studies have found positive effects of electronic technologies (like e-books) on children’s literacy (Korat & Shamir 2008, Korat, 2010). But then we return to ‘that old chestnut’: the cost of such technologies. In all of these conundrums, what becomes apparent is the need for hearty experimentation and research. (Now, six years on from writing this paper, see my digital resource development on the sample Storytime sessions page.)

Kellman (1977) points out that on the one hand, ‘library service to the very young is limited only by the librarian’s imagination’, but on the other hand, ‘developing a program for this age group within the physical and financial confines of individual libraries is a challenge’ (p.100). However, Huebner (2000) concluded, on the basis of her successful study using a inexpensive preschool literacy program, ‘that relatively simple, inexpensive, community-based programs can change the home language and literacy activities of families with young children, including those most likely to begin school less “ready” than their middle-class peers’ (p.291). Furthermore, a study of the Colorado State Library found that following their workshop series, ‘public libraries and librarians throughout the state have earmarked both time and material resources toward enhancing their early literacy programming and services’ (Marks, 2006, p.3), suggesting that professional development may provide greater skills empowerment and motivation for children’s librarians to seek creative ways to overcome time, staffing and financial obstacles. Martinez (2005) similarly found that training aligned librarians’ storytime and outreach efforts with best practices—although a limitation to both studies is that they rely on self-reporting as the measure.

What is exciting is that where money might be a barrier for libraries in improving their PS service, an enhanced service would overcome a monetary barrier for many families. MacLean (2008) argues that ‘public libraries can also act as economic equalisers in the community, … providing literacy-rich opportunities to children who might otherwise miss out’ (p.5). Not everyone can afford—or would prioritise—phonics classes. Interestingly, Korat’s (2005) study found that ‘word recognition and emergent writing were predicted by non-contextual components: phonemic awareness, letters’ names, and concept of print knowledge, and not by contextual knowledge, age, or SES[20] group’ (p.220), which offers hope that a phonics-based PS program may have the potential to enhance all children’s literacy equally, despite their differing demographics. (See also about Nobel Laureate James Heckman’s cost-saving social economics of early childhood investment, in the first early childhood science video playlist on this page.)

Conclusions—Or More Questions?

It seems that there are many unanswered questions relating to the efficacy of PS as a literacy vehicle, and similarly regarding barriers to implementing a practice that nonetheless comes highly recommended. There is a vast amount of research in related fields that strongly suggests incorporating synthetic phonics in PS would make a great contribution to enhancing the literacy of our very youngest members of society and their primary caregivers or “first teachers”. What we need is research and experimentation in a library context. Future research could take many different directions, including surveying parents’ and children’s feelings about current PS practices (and desires for future practices); surveying and/or qualitatively/observationally analysing the dynamic of the parent-child-librarian triad; breaking down current costs and funding specifically for storytime (rather than for CLS in general) and projecting costs for an improved service; surveying librarians’ feelings toward literacy teaching in storytime and attitudes about phonics as a method of teaching reading; closer examination of what librarians are actually taught regarding children and teaching literacy; trialling methods of individual, frequent, intentional librarian professional development in this area, that nests child learning within carer learning within library practitioner learning; trialling methods for enhancing storytime with technological innovation and creative problem-solving; and perhaps most importantly, trialling pilot programs of phonics/literacy based PS to test for clear evidence-based results like we see in education, in the specific area of storytime. As Herd (2000) says, ‘the types of learning experiences naturally suited to public library services and library-community partnerships are those in the area of literacy, the crucial foundation for the learning that takes place both in and out of school’ (para.1), and throughout the lifespan.

References

See also the dedicated Bibliography web page for annotation/abstracts/summaries of these references below.

Adkins, D., & Higgins, S. (2006). Education for library service to youth in five countries. New Review of Children’s Literature and Librarianship, 12(1), 33-48.

Albright, M., Delecki, K., & Hinkle, S. (2009). The evolution of early literacy: A history of best practices in storytimes. Children and Libraries, Spring, 13-8.

Allor, J.H., & McCathren, R.B. (2003). Developing emergent literacy skills through storybook reading. Intervention in School and Clinic, 39(2), 72-9.

Aram, D., & Biron, S. (2004). Joint storybook reading and joint writing interventions among low SES preschoolers: Differential contributions to early literacy. Early Childhood Quarterly, 19, 588-610.

Arnold, R. (2003). Public libraries and early literacy: Raising a reader: ALA’s Preschool Literacy Initiative educates librarians on how to play a role in teaching reading to children. American Libraries, 34(8), 49-51.

Australian Library and Information Association (2010). Statement on public library services to young people in Australia. Deakin, NSW: Australian Library and Information Service. Retrieved from http://www.alia.org.au/policies/young.people.html.

Bing, K. (2009). The role children’s librarians play in fostering literacy in the community. (Masters Dissertation). Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University.

Bundy, A. (2004). Australian Bookstart: A national issue, a compelling case. A report to the nation by Friends of Libraries Australia (FOLA). Australasian Public Libraries and Information Services, 17(4), 196-217.

Bundy, A. (2007). Looking ever forward: Australia’s public libraries serving children and young people. Australasian Public Libraries and Information Services, 20(4), 173-82.

Byrne, B., & Fielding-Barnsley, R. (1989). Phonemic awareness and letter knowledge in the child’s acquisition of the alphabetic principle. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 805–812.

Byrne, B., & Fielding-Barnsley, R. (1995). Evaluation of a program to teach phonemic awareness to young children: A 2- and 3-year follow-up and a new preschool trial. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(3), 488–503.

Carlson, H.L., & Stenmalm, L. (1989). Professional and parent views of early childhood programs: A cross-cultural study. Early Child Development and Care, 50, 51-64.

Celano, D., & Neuman, S.B. (2001). The role of public libraries in children’s literacy development: An evaluation report. Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Library Association.

Cerny, R., Markey, P., & Williams, A. (2006). Outstanding library service to children: putting the core competencies to work. Chicago: American Library Association.

Clarke-Stewart, K.A. (1998). Reading with children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 19(1), 1-14.

Department of Education, Science and Training (2005). Teaching reading: Report and recommendations: National Inquiry into the Teaching of Literacy. Canberra: Department of Education, Science and Training. Retrieved from www.dest.gov.au/nitl/documents/report_recommendations.pdf.

Diamant-Cohen, B., Riordan, E., & Wade, R. (2004). Make way for dendrites: How brain research can impact children’s programming. Children and Libraries, Spring, 12-20.

Dowd, F.S. (1997). Evaluating the impact of public library storytime programs upon the emergent literacy of preschoolers. Public Libraries, 36(6), 346–358.

Duke, N.K., & Kays, J. (1998). “Can I say ‘once upon a time’?”: Kindergarten children developing knowledge of information book language. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 13, 295-318.

Fehrenbach, L.A., Hurford, D.P., Fehrenbach, C.R., Groves-Brannock, R. (1998). Developing the emergent literacy of preschool children through a library outreach program. Journal of Youth Services, 18, 40-45.

Fader, E. (2007). How storytimes for preschool children can incorporate current research. Retrieved from http://www.osbn.state.or.us/OSL/LD/youthsvcs/reading.healthy.families/rfhf.manual/11b.research/11b.1thr8.research.pdf.

Fisher, H. (2000). Children’s and young adults’ service: Like a box of chocolates. Australasian Public Libraries and Information Services, 13(3), 113-18.

Fulton, R. (2009). Taking it to the streets: Every Child Ready to Read on the Go. Children and Libraries, Spring, 8-12.

Gambrell, L.B., Morrow, L.M., & Pennington, C., (2002). Early childhood and elementary literature-based instruction: Current perspectives and special issues. Retrieved from http://www.readingonline.org/articles/handbook/gambrell/.

Ghoting, S.N., & Martin-Díaz, P. (2006). Early literacy storytimes @ your library: partnering with caregivers for success. Chicago: American Library Association.

Gibbs, S.E. (1983). The training of children’s librarians. International Library Review, 15, 191-205.

Hamre, B.K., Justice, L.M., Pianta, R.C., Kilday, C., Sweeney, B., Downer, J.T., & Leach, A. (2010). Implementation fidelity of MyTeachingPartner literacy and language activities: Association with preschoolers’ language and literacy growth. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25, 329-47.

Hargrave, A.C., & Sénéchal, M. (2000). A book reading intervention with preschool children who have limited vocabularies: The benefits of regular reading and dialogic reading. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15, 75-90.

Hatcher, P.J., Goetz, K., Snowling, M.J., Hulme, C., Gibbs, S., & Smith, G. (2006). Evidence for the effectiveness of the early literacy support programme. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 351-67.

Herb, S.L. (2012). Life, literacy, and the pursuit of happiness: The importance of libraries in the lives of young children: The Fourth Follett Lecture, Graduate School of Library and Information Science, Dominican University, 23 April 2008. World Libraries, 19. Retrieved from http://www.worlib.org/vol19no1-2/herbprint1_v19n1-2.shtml.

Herd, S. (2000). Preschool education through public libraries. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/aasl/aaslpubsandjournals/slmrb/slmrcontents/volume42001/herb.cfm.

Hindman, A.H., & Wasik, B.A. (2008). Head Start teachers’ beliefs about language and literacy instruction. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23, 479-92.

Huebner, C.E. (2000). Community-based support for preschool readiness among children in poverty. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 5(3), 291-314.

Johnston, R., & Watson, J. (1998). Accelerating reading attainment: The effectiveness of synthetic phonics. Interchange 57. Retrieved from http://www.scotland.gov.uk/edru/pdf/ers/interchange_57.pdf.

Johnston, R.S, and Watson, J. (2005) The effects of synthetic phonics teaching on reading and spelling attainment, a seven year longitudinal study. Scottish Executive Education Department. Retrieved from http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/36496/0023582.pdf.

Kellman, A. (1977). Services to preschoolers and adults. In S.K. Richardson (Ed), Children’s services of public libraries: Papers presented at the 23rd Allerton Park Institute (pp.99-103). Urbana, Il: Graduate School of Library Science. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2142/1655.

Korat, O. (2005). Contextual and non-contextual knowledge in emergent literacy development: A comparison between children from low SES and middle SES communities. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 20, 220-38.

Korat, O. (2010). Reading electronic books as a support for vocabulary, story comprehension and word reading kindergarten and first grade. Computers and Education, 55, 24-31.

Korat, O., & Shamir, A. (2008). The educational electronic book as a tool for supporting children’s emergent literacy in low versus middle SES groups. Computers and Education, 50, 110-24.

Kupetz, B.N. (1993). A shared responsibility: Nurturing literacy in the very young. School Library Journal, 39(7), 28-31.

Laughlin, S. (2003). Every Child Ready to Read @ your library® Pilot Project: 2003 Evaluation. A Joint Project of the Public Library Association and the Association for Library Service to Children. Huron, IL: Public Library Association.

MacLean, J. (2008). Library preschool storytimes: Developing early literacy skills in Children. Penn State University. Retrieved from http://www.ed.psu.edu/goodlinginstitute/pdf/fam_lit_cert_stud_work/Judy%20MacLean%20Library%20Preschool%20Storytimes.pdf.

Marks, R.B. (2006). Early literacy programs and practices at Colorado Public Libraries. Denver, CO: Library Research Service. Retrieved from http://www.lrs.org/documents/closer_look/early_lit.pdf.

Martinez, G. (2005). Libraries, families and schools—Partnership to achieve reading readiness: A multiple case study of Maryland public librarians. (Doctor of Education Dissertation). Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University.

Marshall, S., & Strempel, G. (2009). Children, early reading and a literate Australia: The role of Australian public libraries. Presented to the ALIA Public Libraries Summit 2009, Retrieved from http://www.alia.org.au/governance/committees/public.libraries/summit09/children.early.reading.a.literate.Australia.pdf.

McGee, L.M., & Schickendanz, J. (2007). Repeated interactive read-alouds in preschool and kindergarten. Reading Rockets. Retrieved from http://www.readingrockets.org/article/16287/.

McKend, H. (2010). Early literacy storytimes for preschoolers in public libraries. Prepared for the Provincial and Territorial Public Library Council. Retrieved from http://www.bclibraries.ca/ptplc/files/early_lit_storytimes_final_english_with_cip_electronic_nov10.pdf.

Milburn, S. (2006, February 13). Inquiry reveals phonics hangup. The Age, Retrieved from http://www.theage.com.au/news/education-news/inquiry-reveals-phonics-hangup/2006/02/11/1139542409947.html?page=2.

Morrow, L.M., & Smith, J.K. (1990). The effects of group size on interactive storybook reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 25, 213-231.

Munde, G. (1997). What are you laughing at? Differences in children’s and adults’ humorous book selections for children. Children’s Literature in Education, 28(4), 219-33.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/nrp/upload/smallbook_pdf.pdf.

State Library of Queensland Public & Indigenous Library Services (2011). Australian public libraries statistical report. Melbourne, VIC: National & State Libraries Australia. Retrieved from http://www.nsla.org.au/publications/statistics/2011/pdf/NSLA.Statistics-20110923-Australian.Public.Libraries.Statistical.Report..2009.10.pdf.

Nichols, S. (2011). Young children’s literacy in the activity space of the library: A geosemiotic investigation. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 11(2), 164-89.

Nicholson, T.W., & Tunmer, W.E. (2011). Reading: The great debate. In C.M. Rubie-Davies (Ed.), Educational psychology: concepts, research and challenges (pp.36-50). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

North, S. (2000). Establishing the foundation of literacy for preschool children: The role of the young peoples services librarian. Australasian Public Libraries and Information Services, 13(2), 52-8.

Ortiz, C., Stowe, R.M., & Arnold, D.H. (2001). Parental influence on child interest in shared picture book reading. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 16, 263-81.

Purcell-Gates, V., McIntyre, E., & Freppon, P.A. (1995). Learning written storybook language in school: A comparison of low-SES children in skills-based and whole language classrooms. American Educational Research Journal, 32, 659-685.

Raban, B., & Nolan, A. (2005). Reading practices experienced by preschool children in areas of disadvantage. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 3(3), 289-98.

Reif, K. (2000). Are public libraries the preschooler’s door to learning?. Public Libraries, 39(5), 262-65 & 268.

Robbins, C., & Ehri, L.C. (1994). Reading storybooks to kindergartners helps them learn new vocabulary words. Journal of Educational Psychology, 86, 54-64.

Rose, J. (2006). Independent Review of the Teaching of Early Reading: Final Report. Cheshire, UK: Department for Education and Skills. Retrieved from https://www.education.gov.uk/publications/eOrderingDownload/0201-2006PDF-EN-01.pdf.

Rosenthal, I. (2004). Leave no library behind: A proposal to “Leave No Library Behind” in the “No Child Left Behind” campaign. Interface, 26(4). Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/ascla/asclapubs/interface/archives/contentlistingby/volume26/leavenolibrarybehind/ALA_print_layout_1_284293_284293.cfm.

Scarborough, H.S., & Dobrich, W., (1994). On the efficacy of reading to preschoolers. Developmental Review, 14, 245-302.

Scheppke, J. (2007). Kids first: How public libraries can survive and thrive in the 21st century. The Bottom Line: Managing Library Finances, 7(3), 35-40.

Sherman, G.W. (1998). How one library solved the overcrowded storytime problem. School Library Journal, 44(11), 36-38.

State Library of Victoria & Library Board of Victoria (2004). Report two: Logging the benefits. Libraries building communities: The vital contribution of Victoria’s public libraries. Melbourne, VIC: State Library of Victoria.

Stuart, M. (1999). Getting ready for reading: Early phoneme awareness and phonics

teaching improves reading and spelling in inner-city second language learners. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 69, 587-605.

Sulzby, E., & Teale, W. (1991). Emergent literacy. In R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research: Volume II (pp. 727–757). New York: Longman.

Sumbler, K., & Willows, D. (1996). Phonological awareness and alphabetic coding

instruction within balanced senior kindergartens. Paper presented as part of the

symposium Systematic Phonics within a Balanced Literacy Program. National Reading Conference, Charleston, SC, December.

Teale, W.H. (1999). Libraries promote early literacy learning: Ideas from current research and early childhood programs. Journal of Youth Services in Libraries, 12(3), 9-16.

Victorian Department of Planning and Community Development (n.d.). Annual survey of public library services in Victoria 2009-2010: Part 2. Local Government Victoria. Retrieved from http://www.dpcd.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/excel_doc/0005/58208/2009-10-Annual-Survey-Pt2.xls.

Walter, V.A. (2003). Public library service to children and teens: A research agenda. Library Trends, 51(4), 571-589.

Wasik, B.A., & Bond, M.A. (2001). Beyond the pages of a book: Interactive book reading and language development in preschool classrooms. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(2), 243-250.

Watson, J. (1999). An investigation of the effects of phonics teaching on children’s progress in reading and spelling. (Doctoral dissertation). Fife, Scotland: University of St Andrews.

Whitehurst, G.J., Crone, D.A., Zevnbergen, A.A., Schultz, M.D., Velting, O.N., & Fischel, J.E. (1999). Outcomes of an emergent literacy intervention from Head Start through second grade. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 261-272.

[1] Geared to 3-5 year-old children. This examination does not include in its scope baby or toddler sessions.

[2] In Fehrenbach, Hurford, Fehrenbach and Bannock’s (1998) research, the mean number of words read by both groups before the study was 0. After just twelve outreach storytime sessions, the control group remained at 0, whereas the experimental group had a mean number of words at 94.

[3] e.g., Teale, 1999, Rosenthal, 2004, Reif, 2000, MacLean, 2008, Albright, Delecki & Hinkle, 2009, McKend, 2010.

[4] e.g., Robbins & Ehri, 1994, Whitehurst, Crone, Zevnbergen, Schultz, Velting & Fischel, 1999, Purcell-Gates, McIntyre & Freppon, 1995, Morrow & Smith, 1990, Duke & Kays, 1998, Hargrave & Sénéchal, 2000, Scarborough & Dobrich, 1994, Ortiz, Stowe & Arnold, 2001, Sulzby & Teale, 1991.

[5] e.g. MacLean, 2008, Albright, Delecki, & Hinkle, 2009, McKend, 2010.

[6] ‘The differences made to an individual as a result of … attending a storytime’ (p.582).

[7] ‘The number of children attending storytimes’ (p.582).

[8] By the Department of Education, Science and Training’s (2005) National Inquiry into the Teaching of Literacy.

[9] By the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s (2000) National Reading Panel.

[10] By what has been dubbed ‘The Rose Report’ (Rose, 2006), commissioned by the Department for Education and Skills.

[11] ‘… librarians focus less on colours, shapes, and letter recognition than on opportunities for children to talk’ (p.12).

[12] What was measured was the degree to which the courses addressed audience (children, young adults/teens/adolescents), venue (public or school libraries), youth as persons, youth librarianship, managing the youth, library (youth materials and youth services) (Adkins and Higgins 2006, p.41)

[13] These theorist are in agreement that ‘public libraries have a unique opportunity to promote school readiness through parental involvement by training the trainer’ (MacLean, 2008, p.5); that often ‘librarians consider caregivers to be the primary audience for [PS] programs’ (Cerny, Markey & Williams, 2006, p.53); and more controversially, that the target audience is parents because PS sessions are neither long enough nor frequent enough to have any significant impact on children’s literacy (Ghoting & Martin-Díaz, 2006).

[14] American Library Association.

[15] National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

[16] ‘The difference between the importance assigned to a service and user satisfaction with it’ (p.260).

[17] Chosen from the International Reading Association’s ‘Children’s Choices for 1995’, the American Library Association’s ‘Notable Children’s Books, 1995’, and the International Reading Association’s ‘Teachers’ Choices for 1995’.

[18] Friends of Libraries Australia.

[19] Providing free books and information kits to new parents.

[20] Socio-economic status.