This website will be under development throughout 2018. Check in periodically for updates.

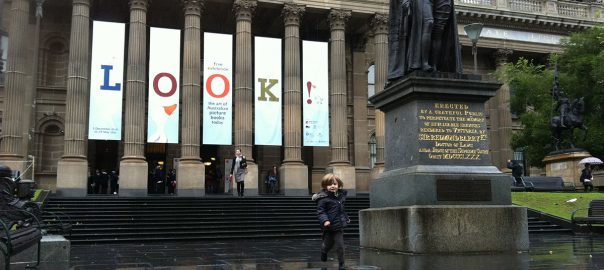

Excerpt from a paper delivered to the State Library of Victoria and Public Libraries Victoria Network on the Abecedarian Approach Australia (3a), May 24th, 2018:

“The fundamental way in which a child’s higher mental functions are formed is through mediated activities shared with an adult or more competent peer.”

– Vygotsky (1986) Thought and Language.

Thanks for inviting me here today to share my reflections on this important work. Speaking to you today is, in a way, challenging. […] I’m invited to talk about my practitioner experience and learnings for this particular project only, no more, no less, so you can make informed choices about whether to pursue this path at your own library services. The trouble is, the most powerful and passionate case I can make, based on my experience and learnings in this particular project, reach far beyond the scope of this project. I think I can inspire you to see the power of the Abecedarian Approach to transform, not just your libraries’ entire approach to family engagement, but your own personal reflexivity as parents, teachers, managers and leaders. 3a techniques are more than just a gimmicky intervention to tick benchmarking boxes and meet strategic commitments. 3a codifies communication and learning principles for lifespan development. Put less formally, it articulates all the successful parenting and mentoring gambits that you all make as educated, privileged people. So what’s the point of learning about something you already do well? The point is to tackle the eternal knowledge management challenge, which is fundamental to our information services industry: the challenge of transmitting tacit knowledge to others. If your skills have been acquired subconsciously and implicitly, how can you explicitly, intentionally, critically mentor others? And, if your successes are implicit and subconscious, then—and here’s the mic drop moment, in the pop culture parlance—your mistakes and missteps are also implicit and subconscious.

While the research tells us that Abecedarian interventions only provide measurable results for at risk families, don’t forget that what has largely been measured is intellectual and health outcomes. Because I had a literate and academically successful mum, I am literate and academically successful, and my son is literate and academically successful for the same reasons. It would seem I’ve got nothing to learn from the 3a techniques. And yet, learning them has transformed not just my professional early childhood practice, but my relationship with my son (who is now 11 and well outside the target range). I can tell you unequivocally that thanks to 3a, I am now a better, more responsive, self-aware parent, with a conscious knowledge of empowering engagement techniques (such as the three Ns and the three Cs) for when I feel lost, incapable, angry, frustrated or impatient: exactly those times when we, as parents, mentors and leaders make hurtful mistakes. No parent can be perfect, nor can most of them be Masters or Doctorate level educators, but all parents can strive, as much as possible, to do no harm. That’s why the enriched caregiving module is my favourite—even though, as a librarian, it probably should be the conversational reading module. I am a mum first, and a librarian always second.

The key reflection I deeply, passionately, desperately want you to take away from today about my experiences in this project are to do with the fundamental 3a pillars of frequent, individual, and intentional interactions. But not in terms of the caregivers’ or educators’ interactions with the child. Crucially, I want to talk about frequent, individual and intentional interactions in terms of parents as the “children” of our librarian mentors, and especially, in terms of librarians as children of our organisations. Everybody benefits from individual, frequent and intentional learning contexts.

In our children and youth team, we have fresh-faced uni graduates and long-term, seasoned staff near retirement. We have team members with studies in teaching but not libraries, libraries but not teaching, people with qualifications and experience in child care, not to mention homeopathy, web design, politics (one team member ran as a Greens candidate some years past), and some have fallen into libraries, and moreover children’s librarianship, not through study, but through the journey of life. We have team members with years of practice, and team members with little practice (as distinct from theoretical learning). Remember that the 2005 Teaching Reading inquiry by the federal government found that only about 10% of teacher graduates had studied explicit literacy techniques in their teaching courses, because they are (bizarrely and tragically) often taught as electives, not core subjects. The same can be said of library courses. Children’s librarianship is at best an elective, covering introductory concepts, with virtually no opportunities to practically engage with children, and at worst the subject area is not present at all–as with my Grad Dip at Curtin Uni. And finally, and this is perhaps one of the most important differentials of all: some people in our team have children, and some do not. This is a dicey thing to say, because we can’t ethically discriminate against non-parents in our library job recruitment any more than we can discriminate against parents. Instead, we have to take responsibility for providing all staff on our teams with the upskilling opportunities to fill the gaps in their practical experience, so that whatever unique background landed them in their children’s librarian role, we know that we are levelling the playing field through individual, frequent and intentional professional development.

The profile I just gave you of our children and youth team is a profile of your own children and youth teams. And that is why my reflections on our rollout of this project are so pertinent. You must, as you carry the baton that we’ve passed to you today, be responsive to the challenges and learnings Paula outlined in her Barrett Reid report. The chief learning was about time. Ie, frequency. Our facilitators felt they needed more time to build trusting relationships with the families, in order to earn the credibility to coach. […]

If you want to see these evidence-based techniques produce outcomes for your at risk families through librarian-caregiver mentoring, then you have to, have to, have to make sure that your librarians have frequent, individual, intentional hands-on practice, so that they are, genuinely, to quote Vygotsky, “a more competent peer” of the caregivers they coach. How do they get this practice without extra money, extra hours, additional contexts for practice outside the existing scope of their library work? By embedding it in everything they do—even if that work is not with vulnerable families, and even if it’s in traditionally group contexts. Practice, practice, practice. Repetition is good, repetition is good, repetition is good. I have spent 18 months since our initial project adapting and practicing 3a exactly for these traditional library contexts, not to take away from our outreach to vulnerable families, or to avoid working in intimate coaching relationships, but to become the more competent peer that I need to be in order to help vulnerable families. […]

Thanks for listening, and I hope to work with you in the future.